Does Death Really Deter?

An essay on the death penalty for drug trafficking in Singapore

The Hanging of an Intellectually Disabled Man

Nagaenthran K. Dharmalingam was hanged in Singapore at Changi Prison on April 27 2023 at the age of 33. Convicted of trafficking 42.72 grams of heroin in April 2009, he was initially scheduled to hang in November 2010, but his execution was put on hold following an unofficial moratorium on hangings in Singapore.

His case drew widespread international attention, with many activists and organisations asking for Singapore to commute his death sentence to life imprisonment due to his alleged low IQ. Yet despite appeals from organisations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, the Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Malaysia, local activists and lawyers, Nagaenthran was still hanged.

In spite of international outrage, in spite of the global abolitionist trend, in spite of his assessed IQ of 69 – lower than the 70 warranting a clinical diagnosis of intellectual disability – and ADHD, Singapore chose to execute a man who was only 20 at the time of his crime, who has since spent his entire adult life in prison.

I was 18 when Nagaenthran’s case made its rounds in the media. I wasn’t politically active then and so didn’t pay too much attention to the outrage and appeals by local activists, but I still remembered asking: What is it about the death penalty that requires it to be applied so unflinchingly? Why can’t just one exception be made for this intellectually disabled man?

An execution is not a matter to be taken lightly, so when Singapore chooses to execute this man despite his diminished culpability, it shows an unflinching commitment towards its laws and the justifications behind them that go far above respecting any individual’s right to life.

Introduction to Singapore’s Death Penalty

The punishment for drug trafficking in Singapore is infamously harsh: under the Misuse of Drugs Act the death penalty is meted out for anyone convicted of trafficking more than

500 grams of cannabis

250 grams of methamphetamine

30 grams of cocaine

30 grams of morphine

15 grams of heroin

as well as for their manufacturing.

While in 2012 Singapore amended the Misuse of Drugs Act to give the court discretion in applying the death penalty when it can be proven that drug traffickers only acted as couriers (not dealers), have substantially assisted authorities in disrupting drug trafficking activities, or suffer from significant mental impairment, the majority of executions in Singapore are still drug-related.

In response to opinion pieces criticising the death penalty for drug offences in Singapore, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs noted Singapore’s close proximity to the Golden Triangle, a hotspot for drug production, and our strong global connections, which increase Singapore’s susceptibility to drug trafficking into and through its borders. The response also cited a 66% reduction in average weight of opium trafficked into Singapore after the death penalty was introduced in 1990, and a 2021 regional study that showed 87.2% of respondents believing that capital punishment deters drug traffickers effectively.

At a dialogue in 2024, Law and Home Affairs Minister Shanmugam also cited a local survey where 66% of Singaporeans polled supported the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking. He framed differences in opinion regarding the death penalty as “position[s] based on ideology,” of which his was that “a state’s obligation is to ensure safety and security… and to save lives,” emphasising that his policies “save more lives than they take away.”

The government cites deterrence and the protection of society as the primary reasons behind the law, and has defended its stance against international criticisms.

This sums up Singapore’s justification behind its drug policy fairly well: a pragmatic one based on the principles of deterrence, occasionally drawing on the support of local opinion and to justify itself to an international audience through an appeal to cultural relativism – an notion in ethics that because different cultures have different traditions, each culture’s rights to traditions ought to be considered valid, even if distinct from “Western-derived” international law norms.

I want to comprehensively question this justification. I will begin with its ideological foundations – cultural relativism, which Singapore attempts to justify through its supposed uniquely vulnerable situation and state sponsored opinion surveys – before addressing the principle of deterrence used to justify the state’s cold pragmatic approach, showing that deterrence is far from the silver bullet for drugs we make it out to be. I will then provide an alternative narrative for Singapore’s relative success in curbing the drug problem, attributing it to its progressive focus on rehabilitation and leniency towards drug victims, before speculating on reasons why Singapore still remains obstinate in its use of the death penalty despite its inhumanity and the the lack of evidence supporting its efficacy.

An Argument Against Cultural Relativism

The notion of cultural relativism has been used extensively by Asian and Islamic governments to justify their rejection, or partial acceptance, of international human rights norms. According to it, irreconcilable cultural differences between societies create substantial difficulties in establishing and realising universal standards for law and morality. Because different cultures have different traditions, and all cultures are equal, the human rights practices for different cultures must be equally tolerated. Hence, in response to “Western-derived” international norms like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), various coalitions of countries have drawn together to create alternative declarations that better suit their own means.

In 1990, 3 years prior to the 1993 Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, foreign ministers of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) met in Egypt to create the 1990 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. This is widely acknowledged as a response to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). However, despite asserting that human rights are “universal [and] indivisible,” it still subjects them to “national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural, and religious backgrounds”. Indeed, the Cairo Declaration, even the updated 2020 version, still fails to guarantee a number of rights stipulated in the UDHR, and is often criticised as an attempt to shield OIC member states from international criticism for human rights violations.

In March 1993, 3 months before the Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, Asian governments also held a regional meeting in Bangkok to create the Bangkok Declaration. While reaffirming the participating governments’ commitment to the United Nations Charter and UDHR, the document likewise contains an implied critique of human rights universalism through articles 8, which while recognising the universality of human rights, contains a conditional qualifier that they must be considered “bearing in mind the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds”, mirroring the Cairo Declaration.

Already here we can begin to see some inherent self contradictions in the practice of cultural relativism. Both declarations, while seeking to reaffirm the universality of human rights, have clauses within them that allow their participating nations independent and contextual – effectively somewhat subjective – consideration of these very rights. While cultural relativism itself is not without merit, having an important protective role in the 1980s in light of imperial incursions from the West (e.g. the Vietnam war), it sets a dangerous precedent when factored into something as fundamental and crucial to our existence as human rights.

A core critique of cultural relativism is its potential to lead to moral nihilism – the belief that there are no objective moral truths. If all ethical values are relative, then we would have no basis for condemning another society for practices like genocide or slavery. For instance, we would be unable to condemn Israel for its genocide of Palestinian people, or North Korea for its adoption of forced labour.

While this is often criticised as an armchair philosopher’s argument, the critique nonetheless remains relevant as in practice, many evidentially harmful practices are still retained and regionally justified through the notion of culture: Female genital mutilation causes severe pain and bleeding, and potentially leads to urinary problems and infections, yet remains practiced in 30 countries across Asia, Middle East, and Africa. Child marriage likewise puts women and children at higher risk of domestic violence and leads to worse economic and health outcomes, yet it is still legal in over 100 countries as of 2016 (no newer statistics).

Moreover, many also agree that the notion of “culture” as put forth by proponents of cultural relativism is problematic: it homogenises the diverse views and experiences of individuals living within a society into a monolithic entity, overlooking those to which this singular definition of “culture” does not apply. This problem is only more pervasive when using cultural relativism as a justification for states and countries to skirt international ethical norms: Moreso than a singular isolated society, a state or country is an agglomeration of its various diverse peoples and cultures that have a claim to its land. What is “culturally relativistic” for a country is merely the political view of the ruling government. Hence to justify its practices and views under a singular definition of “culture” is a slight upon all who have contributed to a country’s historical development.

It would be towards the benefit of the human race for a universally agreed upon standard for human rights to exist. Even if a set of definitions is difficult to arrive at and would require constant change to remain relevant, it still remains exceedingly clear that subjecting any such principles to “regional and local particularities” would only cause harm towards people. Our set of global ethics has historically had a progressive trend, in general moving towards greater rights and protections for the individual, and in criminal sentencing towards progressive and proportional practices focused on rehabilitation. Reflecting this global movement, the death penalty in practice has been abolished in over 70% of countries. The percentage for drug-related crimes is even higher, and yet the death penalty for drug trafficking persists in Singapore, following none of those trends.

Application to Singapore

As of 2024, drug-related executions were confirmed or assumed to have taken place in only six countries: China, Iran, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Singapore. While there are other countries where executions for drug-related crimes are still legal, all but these 6 have either imposed a moratorium on executions – in practice abolishing the death penalty – or have temporarily held off on executions for drug-related crimes (although Iraq is likely slated for more drug-related executions).

While there is not yet clear international consensus on the abolishment of the death penalty as a practice, the international sentiment towards its application for drug-related offences is clear: it is disproportionate, and constitutes cruel and inhumane punishment. Singapore in particular has been criticised by NGOs like Amnesty International and Harm Reduction International, as well as the US and bodies like the EU. Notably, the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has put out multiple statements criticising and calling for halts to drug-related executions in Singapore.

Given such a comprehensive global trend, and the fact that all 5 (or 6) of the other countries practicing drug-related executions are well-known for their human rights violations, Singapore’s continued insistence on practicing the death penalty for drug-related offences seems suspect at best.

Regional Particularities

Despite this, statements by Singapore in response to foreign criticism continue to justify Singapore's use of the drug penalty through “regional particularities” and continued appeals to differences between social norms of Western societies and Singapore. For instance, in response to articles by Lex Lasry and Zach Hope criticising the death penalty, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) cited, among other factors, Singapore’s status as a “small country with a small population”, our proximity to the Golden Triangle, a drug production hotspot, and our good connections with the rest of the world, which provides incentives to smugglers.

While these “regional particularities” may indeed increase our susceptibility to drug problems, these factors are not damning like the statement may make it out to be, and may even be beneficial to an extent: Our small geographical size makes it almost impossible for drug traffickers to set up headquarters off the grid, and our small population increases the effectiveness of enforcement and ease of implementing measures like preventive education. Many of our regional neighbours, despite also sharing our proximity to the Golden Triangle, have deemed it fit to abolish the death penalty in practice. For instance, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia have all imposed moratoriums on the death penalty, with their most recent executions being in 2017, 2018, and 2016 respectively. Our strong global connections are also balanced out by our ability to concentrate our enforcement capabilities on our one airport and two ports, making trafficking difficult and unattractive – as seen in the 2025 UN report on drugs in SEA, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand serve as primary trafficking routes for drugs out of the Golden Triangle, while Singapore remains free from these routes.

Socio-Cultural Differences and the Exceptionalist Narrative

In addition to these “regional particularities”, Singaporean officials also often appeal directly to socio-cultural differences between Western countries and Singapore to justify the death penalty. At a death penalty dialogue session for youths in September 2024 Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam reduced the decision for Singapore to uphold the death penalty to “a position based on ideology… based on values.” He further states that “[he] has slightly different values, which are that a state’s obligation is to ensure safety and security within Singapore, and to save lives.”

The particular wording of this statement here is quite significant: other than making an appeal to cultural relativism, it also reveals an exceptionalist bias towards Singapore distinguishing it from other countries, possibly influencing its decision to flout international human rights norms. Shanmugam claims that he has “slightly different values,” presumably from other countries, on the role of the state, which he believes is to “ensure safety and security” and “save lives.” With this statement, one naturally wonders what these “different values” other countries hold may be: Do other countries not believe that the state ought to ensure safety and security and save lives? Do they flout the livelihood and wellbeing of their citizens in the name of upholding human rights? Surely not.

Yet this exceptionalist narrative is only further shown in another of MFA’s statements, this time in response to UN human rights experts calling for Singapore to halt the death penalty, where it is stated that Singapore “does not have the liberty to experiment with the lives of [it’s] people.” Experiment is another interesting word choice, because it implies a view that countries who abolish their death penalties do so recklessly as part of testing for certain hypotheses, with little to no prior justification to back their views. This cannot be further from the truth: the bulk of existing research suggests that the evidential support for deterrence is spotty at best, and in almost every instance where the death penalty has been abolished, countries and states that did so saw an overall decline in crime rates in the years following abolition. It is Singapore, ironically, who fails to recognise this, and remains stubbornly uncompromising in its position to uphold the death penalty for drug-related crimes.

Socio-cultural or ideological differences should not, and do not, make Singapore an exception to international human rights norms and the evidence-based research running counter to its current practices. Allowing them to do so would be actively harmful for the nation as it stymies its progress towards making positive changes for itself.

Public Opinion

Lastly, Singapore often cites its public opinion surveys on the death penalty to justify its current legislation. Shanmugam in his dialogue cited a local survey where 66% of Singaporeans polled supported the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking, and the earlier MFA statement also cited a regional survey where 87% of respondents believed that capital punishment deters people from trafficking significant amount of drugs into Singapore, and 83% believed that capital punishment is more effective than life imprisonment in discouraging people from trafficking drugs.

Singapore historically has also used public opinion to justify its retention of the death penalty. Vivian Balakrishnam, 2016 Foreign Minister, stated that “There are very high levels of support on the part of our people for the death penalty to remain on our books,” and in 2007, then Deputy Prime Minister Shunmugam Jayakumar also said that “the death penalty is the will of the majority.”

To address the elephants in the room: Opinion surveys are not evidence that the death penalty works. Public opinion is often misinformed. We need stronger justification than this when we choose to condemn someone to death for a non-violent crime. Opinion surveys are simply what they are – surveys of opinions. Nonetheless, it is important for these surveys to be addressed as Singapore is a parliamentary democracy, and public opinion is a factor that will inform the policy decisions of officials.

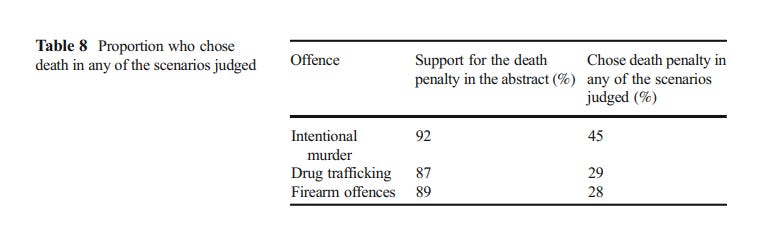

To begin, studies showing high percentages of support for the death penalty often obtain them through asking simple generalised questions, such as “The mandatory death penalty is appropriate as the punishment for trafficking a significant amount of drugs,” used in Shanmugam’s quoted 66% MHA study. However, these percentages are extremely misleading, as when presented with specific scenarios qualifying for the death penalty, support for it always drops dramatically.

In a 2018 study by SMU which found 87% support for the death penalty for drug traffickers (54% discretionary 33% mandatory**), upon presenting participants with specific scenarios for drug trafficking, the highest proportion favouring the death penalty, in a scenario with aggravating factors was only 47%. The other three scenarios found support ranging between 17-33%, revealing in practice a minority support for the death penalty for drug trafficking. This result is consistent with other public opinion studies on the death penalty for drug trafficking: A Malaysian study showed a discrepancy of 80% (generalised) and 29% (highest of 4 scenarios, with aggravating factors), and a Chinese study showed a discrepancy of roughly 55% and 12%. In addition, the SMU study also showed that amongst those who supported the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking, less than a third of them chose the death penalty for all scenarios .

**The MHA study does not give an option for participants to indicate support for a discretionary death penalty, presenting a false dilemma where participants are forced into absolutist positions. This likely plays a part in the large 33-66% discrepancy between the MHA and SMU study.

There is an option to indicate support for the discretionary death penalty later, but that question is only asked IF and AFTER participants answered neutral/disagree to the previous question.

The SMU study also shows that despite seemingly strong support for the death penalty, most participants in practice hold apathetic sentiments towards it – only 5% indicated “very interested or concerned,” and 54% indicated that they “never talk about it,” with 32% only discussing it “at most once a year.” Participants were generally also poorly informed on the death penalty – 62% indicated that they knew “little” to “nothing about it,” and when quizzed on the number of executions in the last 10 years, only about 30% of participants managed to give an estimate within a 50% margin of error. This is again mirrored in the Chinese study, where 70% of respondents indicated low interest and knowledge as opposed to the 55% support, and the Malaysia study, where less than 10% indicated high concern and over 50% indicated poor knowledge despite the 75% support.

Moreover, attitudes towards the death penalty are easily changeable if the expectations of deterrence and incapacitation are fulfilled by other alternatives. In the SMU study, when participants were asked if they would change their minds if “new scientific evidence proved that the death penalty was not a better deterrent than life or very long imprisonment,” 50% of participants who initially supported the death penalty for drug trafficking changed their mind. This is again supported by the Chinese study which shows support falling to 29% when offered life without parole (LWOP) as an alternative, and further down to 24% when offered LWOP with restitution (fulfilling compensation). The Malaysian study likewise shows support falling from 75% to 43% for drug trafficking if it was shown that death was not a more effective deterrent than life in prison.

Indeed, it seems that support for the death penalty in Singapore (and other regional countries) often takes on more of an expressive or symbolic role than an instrumental one based on concerns of crime – despite knowing little and holding apathetic attitudes towards it, our default stance is to support the right of the state to kill, rather than to value the sanctity of human life. An explanation for this phenomenon is attitudes of authoritarianism and conservatism – common in Singapore, Malaysia, and China, and linked to support for punitive punishment – which have been confirmed by numerous studies to correlate with support for the death penalty. When citizens have grown up taught and exposed to the authoritarian tendencies of the government, and especially in Singapore fed praises on the government’s harsh punitive punishments, there is an air of manufactured consent around our acceptance of the death penalty. That is why the knee-jerk response to any question of the death penalty is often a resounding yes, yet falls apart upon further questioning, and why any reference to public opinion surveys in support of the death penalty are but irrational exercises in circularity.

Very clearly, public opinion is not a barrier to legislative change. It is simply a crutch to lean on, along with our purported socio-cultural differences and regional particularities, in absence of any substantial evidence on the death penalty’s deterrence effect, which the next section will address.

A Case Against Deterrence

The theory behind deterrence Singapore employs to justify its harsh drug law is as such: more and tougher punishments deter crime because people will consider the consequences before choosing to commit them. This appears simple and intuitive – if the punishment for robbery contains a long prison sentence and caning, a potential robber would likely be deterred from robbing someone because the risk of incurring the costs of getting caught far outweighs the potential benefit they stand to gain from crime. Likewise for drugs, people would not be motivated to traffic drugs because the harsh punishments of death or lengthy imprisonment outweigh the monetary benefits they stand to gain from it. However, deterrence theory is problematic: other than the spotty evidence supporting its efficacy, deterrence also suffers from many theoretical problems severely limiting its function, especially in the case of drug crimes.

The first and most obvious would be the assumption of human rationality, that people choose to commit crimes based on the potential costs and benefits of it. While this may be true for certain types of criminals, such as those looking to make a quick buck off scamming or robbing people, the socio-economic conditions surrounding drug use and trafficking renders this assumption void in the majority of cases. Most traffickers are not members of criminal syndicates or profit seeking individuals driven by greed – many are individuals in less fortunate situations that have been coerced or forced by their situations (e.g. poverty and debt) into crime. Many more succumb to it as a result of social pressure, or out of necessity to fund their own addictions. These factors diminish their ability to rationally consider the consequences of crimes, leading them to traffic drugs despite the heavy cost to potentially be incurred.

Another problem would be not factoring in the cost and benefits of non-crime as well as crime. Even if the costs of crime are high, if there is a substantial cost and lack of benefit to non-crime behavior, then a rational cost-benefit analysis could still see a person choosing to engage in criminal behavior. This is again especially applicable to drug crime – when people in poverty traffic drugs, they do so not just for the money, but also because the cost of not engaging in crime entails a helpless continuation of their current situation. For prior offenders too, if their criminal record makes it difficult to find employment, or if they lack meaningful connections outside of prison to maintain, the benefit in non-crime behavior would be minimal. In both of these cases, crime would appear very attractive, even with severe potential punishments.

Lastly would be the complexity of the cost-benefit analysis deterrence theory presumes – other than just the severity of punishment, the certainty and swiftness of punishment must also be considered. Unlike other crimes like robbery or kidnapping, which have high probabilities of arrest and conviction, drug crimes are difficult to monitor and track due to the complexity of smuggling networks, and cooperation between suppliers and buyers to avoid detection from authorities. As a result, almost all drug traffickers and dealers would commit multiple offences before getting caught (if ever). The low chance of arrest with each individual instance of crime undermines the deterrent effect of harsh punishments through a low certainty of punishment.

This problem is magnified by the social conditions of drugs – because vicarious (lived through others) experiences affect our perception of the cost and benefits of crime, when people see drug traffickers within their social circles making bank while avoiding punishment, their perceptions of the benefits may be augmented while that of the costs diminished, further incentivising them to commit crimes.

These reasons and more make deterrence extremely unlikely to have any significant effect on drug crime (and most crime in general). While MFA does has a statistic it likes to cite to support the deterrent effect of the death penalty – a 66% reduction in average net weight of opium trafficked before and after 1990 when the death penalty for opium and cannabis was implemented (cited in a reply to UN officials) – the statistic is a curious one: instead of citing a direct fall in the number of drug trafficking cases, which would provide more direct and concrete evidence for deterrence, why did MFA cite a weight reduction statistic instead?

A look at the Ministry of Home Affairs study that was the source of this statistic reveals the obvious answer – there was no significant change in drug trafficking cases in the 4 year periods before and after 1990 when the death penalty was implemented for opium trafficking (there was a small increase actually, 25 -> 28 cases, but this is statistically insignificant). Additionally, the percentage of traffickers trafficking above the death penalty threshold for opium (1.2kg) remained almost exactly the same (80% -> 78%). The same trend was observed for cannabis trafficking, where the 4 year periods before and after 1990 when the death penalty was implemented produced the exact same number of cases (101 -> 101), and insignificant change in the percentage of traffickers trafficking above the threshold (0.5kg, 25% -> 24%). This shows that, contrary to what the MFA attempts to imply, the implementations of the death penalty did not have any impact on drug trafficking crime rates.

While it is true that there were significant decreases in the average weight of opium and cannabis trafficked (40.7kg to 13.7kg and 1.5kg to 1.1kg respectively), I disagree with the study’s conclusion that the death penalty likely had a deterrent effect on trafficking behavior. If we presume that drug traffickers are rational actors, it would make no sense for them to reduce the net weight of drugs they traffic while remaining above the death penalty threshold as the potential cost for them remains the same while their profit decreases. While the study employed a difference-in-difference analysis to show that certain demographics of cannabis traffickers became less likely to traffic above the 0.5kg threshold after 1990, the lack of change in the overall case statistics reflecting this trend shows that traffickers who changed their behaviors to stop or traffic less were simply replaced by other traffickers who were willing to risk the death penalty. This phenomenon is consistent with other studies showing that due to the readily available supply of drug dealers, driving existing suppliers off the market – whether through incarceration or the threat of punishment – will only create an environment for new suppliers to enter the market or allow existing suppliers to expand.

Another possible explanation is that the fear of getting caught would lead traffickers to traffic lower quantities, which would be easier to hide. I disagree with this too, as if fear of punishment was what was truly driving the change in trafficking behavior, you would expect to see a greater proportion of traffickers trafficking under the death penalty threshold. The statistics show clearly that this is not the case.

I contend instead that this fall in the quantity of drugs trafficked was caused more by demand side factors from consumers of drugs, shrinking the market available for traffickers to make a profit. Leading up to the introduction of the death penalty in 1990, government agencies had begun stepping up enforcement for drug addicts – seen through a 30% increase of drug addicts arrested from an unspecified number in 1987 to 5451 in 1988. This is also reflected in the increase in Singapore’s prison population, which rose from 2,522 in 1982 to 4,140 in 1986 and 5,476 in 1990. Additionally, in the 1989 Misuse of Drugs Act amendment, other than introducing the death penalty, the government also increased the mandatory jail term for repeat drug consumption offenders from a minimum of 2 to 3 years. This change in attitude in favour of further incarceration was once again reflected by the increase in prison population, which grew almost 200% from 5,476 in 1990 to 15,344 in 1995**. This number still does not include the amount of abusers in rehabilitation centers, which increased by 2,000 between 1990 and 1994, and also changed their philosophy to favour incarceration, keeping “hardcore addicts… progressively longer.”

**Juvenile arrests were on the rise in this period, rising from 1,205 to 2,589 between 1990 and 1995, but cannot really compare to the 6,000 drug abusers arrested annually. Juveniles are also less likely to be incarcerated. Additionally, general crime rates were decreasing.

An increase of at least 10,000 abusers incarcerated and even more arrested is certainly enough to put a dent in drug demand in Singapore. Additionally, the stronger public stance taken by the government towards drug abuse could have catalysed a shift in public opinion away from drug use, further reducing demand. All this provides strong support for an alternative conclusion that a decrease in demand is what caused the decrease in drug quantities trafficked, rather than deterrence affecting supply.

However, all this is not to say that incarceration itself is the reason behind Singapore’s general success at achieving a drug-free society – our regional neighbours have employed similar strategies using deterrence and incarceration, but are still regarded to have failed in their wars on drugs. Rather, I think the credit belongs to Singapore’s early recognition of the nuances of the drug problem, and taking appropriate actions to address them.

Singapore’s Success

Even back in the 1990s, where incarceration for drug offenders was at its peak, Singapore had already been investing significant resources into treating and rehabilitating drug abusers for two decades prior – the Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) was established in 1971, and the Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association (SANA) was set up in 1972 to complement CNB’s efforts. Together they constituted a dual-pronged approach, where CNB focused on enforcement efforts, while SANA worked to promote preventive public education and provide recovering addicts with counselling and aftercare services.

A speech by Mr Wong Kan Seng in 1994, then Minister for Home Affairs, also showed this understanding of nuance. Other than emphasising the necessity for preventive education and aftercare support, he also discussed the role of the community in preventing relapses. In his words, “If an addict perceives that his family and the community in general do not accept him or has given up hope on him, then no amount of rehabilitation or aftercare is going to help him at all.” So true Mr Wong.

He also differentiated between “hardcore addicts” (third timers or more) and first-second time abusers, showing nuance in the way drug abusers were criminalised and treated. This view is reflected in the way CNB treats its drug abusers today – abusers caught purely for consumption offences are usually sent for treatment and rehabilitation rather than being charged in court. First time offenders deemed to be at low-risk for reoffending can also be put under a community based rehabilitation plan by SANA rather than being sent to the Drug Rehabilitation Center (DRC). Even if sent to the DRC, once the DRC regime is completed, abusers will be released without a criminal record. All this allows for easier reintegration into society, reducing recidivism rates.

The system comes with many of its own flaws however – a series by Transformative Justice Collective details the dehumanising conditions of the DRC, the systemic discrimination against sexual minorities and inmates of lower socio-economic statuses, as well as apathetic and abusive staff. Yet, compared to Malaysia, which throws even first time drug offenders straight into prison, the current focus of Singapore towards rehabilitation is a progressive one.

It is not deterrence, incarceration, or any punitive measure that lets Singapore have its drug-free success. It is the use of evidence-based policy solutions allowing rehabilitation and reintegration that has earned Singapore its status as a global success story in drug enforcement.

Why the Death Penalty Then?

Even in light of the above arguments against the death penalty, against the effectiveness of deterrence, and an alternative narrative accrediting Singapore’s success to its progressive policies, one can still find reasons to support the death penalty.

Society’s Perspective

Retribution is the final societal perspective I will consider in this article. It is mentioned last due to its relative irrelevance towards achieving pragmatic outcomes in policy, but nonetheless remains important and prevalent due to its appeal to our intuitive sense of justice. Applied to drug trafficking, to punish the trafficker would be to seek retribution for all the harm those traffic drugs would have inflicted onto society.

Almost immediately upon examination though, this logic begins to fall apart. Retribution functions on the logic of “an eye for an eye,” but drug traffickers caught with their drug packages have yet to inflict any harm upon society, so imposing the death penalty on them would not make sense. Unless it can be proven that they have previously trafficked drugs into Singapore, or were successful in distributing their packages, imposing the death penalty would be logically incompatible with retributive theory.

Imposing the death penalty for drug traffickers would also be inappropriate because it pins the weight of society’s vengeance on one group of people despite it being an entire complex system that enables drugs to do the harm it does (producers, traffickers, local distributors, buyers and users). They ought to be at most saddled with a lengthy prison sentence for their partial role in the supply chain, not something as harsh and irreversible as death.

Moreover, retributive justice in the form of the death penalty disproportionately punishes traffickers who lack awareness of Singapore’s harsh drug laws, are less experienced, and who are more likely to be coerced or situationally forced into drug trafficking (e.g. to pay off debt). Repeat traffickers familiar with enforcement techniques and aware of trafficking thresholds almost certainly cause more societal harm than new traffickers, but can avoid the death penalty even if caught due to their knowledge of legal thresholds. Hence, punishing traffickers who are caught with the death penalty results in a disproportionate amount of our ire directed towards those often the least (or not the most) deserving of it.

Retributive justice theory does not support the use of the death penalty to punish drug traffickers as it is logically inconsistent with the theory, disproportionate to their role in the supply chain, and almost always disproportionate to the harm they have caused society. This is not to say that drug traffickers should be simply set free however, but that death is too severe a punishment for retribution when keeping in mind all the above factors.

Government’s Perspective

Disclaimer: these are opinions (maybe) (don't POFMA me)

The government however does have some possible reasons for supporting the death penalty. The PAP has historically been very pragmatic and open towards adopting evidence-based, sometimes drastic solutions for problems. Yet when it comes to the death penalty, it remains obstinate in its retentionist stance. Why is this the case?

In my opinion, when it comes to governments and politicians, true “stupid decisions” are few and far between. If something they do seems irrational and leads to negative outcomes for society, the true motivations behind it are almost always political. To me, the insistence on a very harsh and public stance of deterrence is part of their perpetuation of a crisis narrative, where Singapore is portrayed to be vulnerable and under permanent, immutable threat, justifying its wide range of restraints on our democratic freedoms.

This narrative is apparent to anyone who has been put through our national education system in the past few decades – from young we were taught that Singapore is especially vulnerable due to its small size, lack of natural resources, our unique ethnic makeup and more. Yet, in a 2011 lecture at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman opined that some of Singapore’s key strengths were in fact its small size and lack of natural resources, which allowed it to forge political consensus easily and escape the resource curse that has so plagued many other countries. Our vulnerability is not so much an objective fact as it is a matter of perspective, or a social construct created by those in power.

The drug problem as so written by the authorities is but another manifestation of this narrative – the very factors bemoaned by the MFA in its responses to foreign criticisms are far from damning, and can even be beneficial towards us. By framing the drug problem as an external, cultural, existential threat, the state cultivates a culture of fear and uncertainty, manufacturing consent for their “clear and strong mandate,” which is in essence their ability to push forward bills and changes without significant resistance from political opposition or the public.

This also turns our attention from away from the true causes of drug dependency, which are systemic problems rooted within the structure of our society: issues like poverty, lack of support, poor access to healthcare leading to self medication, and more. As a result, Singaporeans rally around the state’s punitive measures rather than look introspectively towards the society we live in, questioning the state’s policies and decisions.

Pushing forth the death penalty can also be a means for the PAP to garner support from the conservative leaning population in Singapore. While Singapore fortunately does not suffer from the problem of drug related populism present in some neighbouring countries, it nonetheless continues to demonise drug culture and dehumanise drug users, allowing it to manufacture consent for harsh punitive punishments, which appeal to a conservative voter-base. This view of drugs also keeps it as a political rally point against liberal movements, which they are commonly associated with.

We offer drug abusers multiple chances to reintegrate back into society without criminal records, employ progressive evidence-based policies to support recovering abusers, but yet very publicly advocate for the mandatory death penalty for traffickers, despite evidence pointing towards its inefficacy. This inconsistency to me speaks strongly of political posturing, where the government maintains its stance on the death penalty for public support or approval, rather than genuine policy impact. It is disingenuous and damaging to our society, as it holds Singapore back from making evidenced-based policy decisions that benefit us and better respect human rights standards across the world.

Conclusion and Closing Remarks

In all, this article attempts to examine the various forms of justification used by the Singapore government to justify its continued use of the death penalty for drug traffickers – from questioning ideological justifications, disputing the often cited 1990 opium statistic, to providing an alternative narrative to explain our relative success in achieving a drug-free country, I hope this article offers a convincing argument for the abolitionist camp in Singapore from a fresh perspective.

Many drug traffickers are often victims of addiction themselves, who end up trafficking due to inevitable social or financial pressures. If we believe in rehabilitating drug users, we should then also believe in helping traffickers escape their circumstances to restart their lives. They are people too, and I do not think it is right if just because they have committed a crime – trafficking a certain quantity of drugs past an arbitrarily imposed threshold – we deem it acceptable to reject their humanity and kill them.

Hence, even if the government continues to adopt deterrence as the primary philosophy in its drug laws, my view is that the maximum sentence for drug trafficking should be reduced to life with parole – harsh enough to deter any rational trafficker evaluating crime on a cost-benefit scale, but still providing opportunity for people to turn a new leaf should they wish.

As for my personal stances, I am not pro-drugs. I think drugs are harmful to society and that recreational drug use should be strongly discouraged. I did praise the government’s rehabilitative approach through the DRC rather than prison, but the center itself and its regimes are still very much inhumane and require a lot of change (do read the TJC articles on it).

I am not necessarily anti-establishment either. I believe the PAP is capable of keeping SG safe and prosperous for years to come. I simply want it to do better, to have more checks and balances, and to have a greater respect for our lives and voices. My voice and vote will hence go towards movements and parties that push it to do so.

Yeah that’s about it. This is just my personal substack with my own takes, arguments, and research. I enjoy writing and reading, and this article is my way of advocating for a cause while having a good (read: intellectually stimulating but also frustrating) time. I might write one more article on the government’s portrayal of drug use eventually, but after two articles I think I’ll write something new first before coming back (thinking of animal cruelty).

Hope y’all enjoyed :3

Link to my first article (also on the death penalty)